Author Essay: Jennifer Latham on writing Dreamland Burning

Before the gunfire and flames, there was a hand-stitched dress—fitted and fine—that made Veneice Dunn feel beautiful. On May 31, 1921, she wasn’t thinking about how attacks on black communities had rocked Atlanta, St. Louis, Omaha, and Chicago in recent years. Or about how willing Tulsa law enforcement officials were to turn a blind eye to vigilante “justice.” Or even about Dick Rowland, the young black man arrested in Tulsa that morning on a more-than-questionable charge of “assault” on a white woman. Veneice was a junior at Booker T. Washington High School, and she was thinking about her prom.

But that very afternoon, a white friend of her father’s drove to the Dunn’s home in the thriving black section of Jim Crow-segregated Tulsa called Greenwood. He told them a crowd of angry white men with the makings of a lynch mob had gathered in front of the courthouse where Rowland was imprisoned. There were rumblings the evening’s planned violence wouldn’t stop with a lynching, he said. Greenwood was at risk, and the Dunns should stay with him in the country until the threat passed.

So Veneice packed a small bag, laid the lovely blue gown on her bed, and prayed her prom would go on the next evening as planned.

It didn’t.

By mid-afternoon on June 1, the Dunn’s home had been looted and burned by white rioters, along with twelve hundred other residences and businesses. “America’s Black Wall Street” lay in ashes, and at least three hundred people—most of them black—were dead. Veneice never danced in her gown, and she spent years to come dreading the prospect of seeing it on a white woman downtown.

Even though the Tulsa race riot (which many Tulsans now refer to as a race massacre) was possibly the worst in US history, it left barely a ripple as it disappeared beneath our collective conscience. In fact, I’d lived here nearly three years before I even heard about it. Once I did, though, I needed to know more.

Unfortunately, there aren’t many books on the subject. The ones out there are excellent, but the sad truth is that not much was written about the violence when it occurred, and much of the documentation was destroyed. Those photos and letters and articles that remain take up only a few legal boxes in the University of Tulsa’s archives. Even the June 1 Tulsa Tribune editorial that reportedly called for Dick Rowland’s lynching was physically torn from the Tribune’s own archived copy. To this day, no one knows for sure what it said.

Still, some survivors’ stories live on. A few, like Veneice’s, were published. Others are preserved on audio and video recordings of the survivors themselves. Every one of them will break your heart.

Honestly, my brain is Teflon-coated when it comes to remembering dates and timelines. But the survivors’ stories I found sank in deep and inspired me to write Dreamland Burning. Over four years of research went into it, and yes, Veneice’s dress does make a brief cameo appearance toward the end. But since I knew from the start that it would be wrong to speak for survivors who have already spoken for themselves, my characters are purely fictional. They tell their stories on behalf of those who didn’t survive the riot, as well as those who lived but were never heard. I hope William and Joseph and Ruby speak truth to readers. I hope they make people want to learn more about the riot. And I hope that maybe—possibly—they might even break a few hearts…and mend them right back up again.

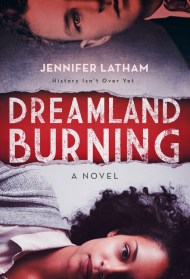

A compelling dual-narrated tale from Jennifer Latham that questions how far we’ve come with race relations.

Some bodies won’t stay buried.

Some stories need to be told.

When seventeen-year-old Rowan Chase finds a skeleton on her family’s property, she has no idea that investigating the brutal century-old murder will lead to a summer of painful discoveries about the present and the past.

Nearly one hundred years earlier, a misguided violent encounter propels seventeen-year-old Will Tillman into a racial firestorm. In a country rife with violence against blacks and a hometown segregated by Jim Crow, Will must make hard choices on a painful journey towards self discovery and face his inner demons in order to do what’s right the night Tulsa burns.

Through intricately interwoven alternating perspectives, Jennifer Latham’s lightning-paced page-turner brings the Tulsa race riot of 1921 to blazing life and raises important questions about the complex state of US race relations–both yesterday and today.