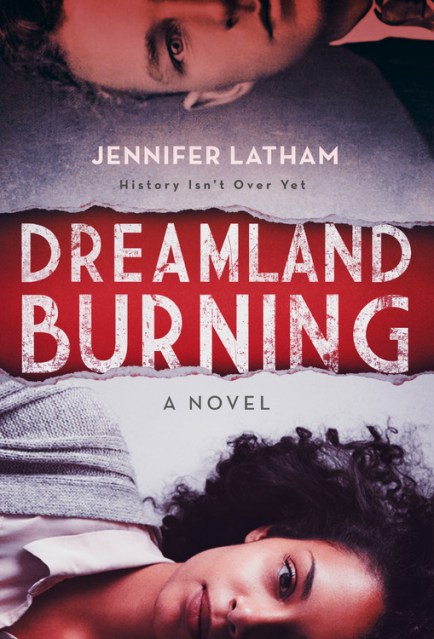

Dreamland Burning

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- ebook $8.99 $11.99 CAD

- Hardcover $36.99 $46.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

Also available from:

A compelling dual-narrated tale from Jennifer Latham that questions how far we’ve come with race relations.

Some bodies won’t stay buried.

Some stories need to be told.

When seventeen-year-old Rowan Chase finds a skeleton on her family’s property, she has no idea that investigating the brutal century-old murder will lead to a summer of painful discoveries about the present and the past.

Nearly one hundred years earlier, a misguided violent encounter propels seventeen-year-old Will Tillman into a racial firestorm. In a country rife with violence against blacks and a hometown segregated by Jim Crow, Will must make hard choices on a painful journey towards self discovery and face his inner demons in order to do what’s right the night Tulsa burns.

Through intricately interwoven alternating perspectives, Jennifer Latham’s lightning-paced page-turner brings the Tulsa race riot of 1921 to blazing life and raises important questions about the complex state of US race relations–both yesterday and today.

- On Sale

- Feb 20, 2018

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9780316384902

About the Author

Jennifer Latham is an army brat with a soft spot for kids, books, and poorly behaved dogs. She’s the author of Scarlett Undercover and lives in Tulsa, Oklahoma, with her husband and two daughters.

Peek the Audiobook

#DreamlandBurning

On the Blog

-

Historical Fiction to Read Based on Your Zodiac Sign

-

Historical fiction for every kind of reader

-

Historical fiction to feed the part of your soul that just wants to dress up in a fancy gown and stare out a window forlornly

-

7 Audiobooks That Will Fill Your Ears with Heavenly Sounds

-

Historical Fiction That Will Take You Back in Time

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use