The Deep Bottom Drawer: A Conversation with Lois Duncan

I’m just beginning to realize the flickering presence Lois Duncan’s books still play in my imagination, decades after discovering them.

I’m just beginning to realize the flickering presence Lois Duncan’s books still play in my imagination, decades after discovering them.

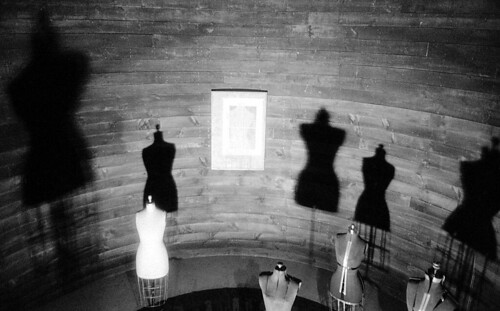

Most of my reading life, age nine to twelve especially, seemed to be in search of books that somehow conveyed for me, as movies did, a world as dark and tangled and mysterious as the one I glimpsed in my fevered girl head. These were books of shadows, books where the every day—banging school lockers, fights with siblings, sprawling out on the carpet and watching TV—could, at any moment, give way to darkness, beauty, terror, a Grimm’s fairy tale of precipice-peering and descent. The same things I found, and clung to, in true crime and noir.

It was not until a few years ago that I discovered her non-fiction recounting of her daughter’s (still officially unsolved) murder and its aftermath, Who Killed My Daughter?, which is wrenching, unforgettable book. It’s hard to talk about such a personal book, written by a grieving mother, in objective terms, but, to try, it’s also a fascinating book as Duncan undertakes her own investigations, both traditional and untraditional, including working with a psychic.

Now, with the reissuing and updating of ten of Duncan’s YA books, including my favorites, I was fortunate enough to interview the author herself. On a personal level, there’s something deeply satisfying and more than a little uncanny about it because, as with so many interviews, I came to feel I was revealing (or at least realizing) as much about myself (maybe more) as the author herself was. Most of all, though, I came away feeling deeply inspired by her path as a female author with such a long career in a famously punishing business. The author of 50 books, she has endured countless “revolutions” in publishing and never let any of it stop her from creating, from experimenting, from, well, telling the stories she wanted to tell.

Speaking via a series of emails, we began by talking about the new editions. She told me how exciting it was for her to update the new editions, adding, “I’ve been astonished to realize how well the characters and plots have transcended the years. All I really had to do was tweak the stories in order to change hair styles and dress and give my protagonists access to the technical toys of today—cell phones, computers, digital cameras, etc. That gave me a sense of power. It was like rebirthing my children and being able to provide them with wings.”

Speaking via a series of emails, we began by talking about the new editions. She told me how exciting it was for her to update the new editions, adding, “I’ve been astonished to realize how well the characters and plots have transcended the years. All I really had to do was tweak the stories in order to change hair styles and dress and give my protagonists access to the technical toys of today—cell phones, computers, digital cameras, etc. That gave me a sense of power. It was like rebirthing my children and being able to provide them with wings.”

Megan: I am a tremendous fan, and have been since I first found your books in the early 1980s, as a young girl in suburban Michigan. It’s a big thrill to see these reissues and to get to revisit these wonderful books and also, somehow, the 10-year-old me who so savored them.

One of the things that strike me now, re-reading them, is how they managed to mingle the everyday (family chores, pesky siblings) and identifiable with the strange, the paranormal, darkness itself. I think it can speak to young girls’ sense that they want to be invited into a book (e.g., a heroine they feel is like them), but they also want to visit murky places. Explore, uncover the unknown. Was that “mix” one of your aims when you wrote them? How could you be sure the darker themes would be speak to readers?

Lois Duncan: I wasn’t sure. And, at first, my editors weren’t either. A Gift of Magic (my first novel that involved ESP) was rejected seven times before Little, Brown daringly published it. The other publishers were certain that young readers would not be interested. I get great satisfaction from the fact that the book, originally published in 1971, has never gone out of print and becomes more and more popular.

As far as my style goes—I think the fact that the books involve “normal” kids in “normal” life situations creates a realistic format that the average reader easily relates to. As paranormal events begin to occur, the viewpoint character finds them just as bewildering as the reader. Then, as that character begins to accept them, the reader does so also, because he or she is following the same thought process.

Megan: That makes so much sense, and explains the uncanny quality—everything feels so familiar except something is off, something is just slightly askew, and the heroine must push further, pursue. Her pursuit mirrors ours.

I’ve been thinking a lot about how powerful “doubling” appears in your books, especially Summer of Fear and Stranger With My Face. Reading them now it feels like the double almost serves as this valve or outlet for the heroine. She does some of the things the heroine would be afraid to do (and feels things—like anger—that the heroines may not feel comfortable expressing). These doubles get what they want, or nearly do. In Stranger, Laurie, ironically, starts to make positive changes in her life (dumping her spoiled boyfriend and his mean clique) after the dangerous double enters her life—as if the double empowers her in some strange way.

Do you think teen readers (or teen girl readers) might especially respond to this idea of a double, someone like us but not quite?

LD: This reminds me of when I was in my 40s and teaching magazine writing for the Journalism Department at the

University of New Mexico. I was hired on a fluke. The professor who was scheduled to teach the course became ill, so the chair of the department, my personal friend Tony Hillerman, asked me to fill in for a semester. Tony knew I’d never been to college and didn’t care; he just knew I’d written successfully for magazines for years. The original professor never returned, and someone else replaced Tony as Chair and automatically kept me on. I discovered I loved teaching writing and started to get worried that my deep dark secret, (no college!) might be discovered, so I began taking courses under my married name, Lois Arquette, hoping I could get a degree before someone “outed” me. In the course of that endeavor, I took a juvenile literature class where they were studying “Lois Duncan books.” My fellow students were excitedly writing A-plus papers about how many of my books were based on Greek myths. I had never even read those myths!

Often the reader finds in a book what that reader is looking for, which may not be at all what the author meant to put there. The author-reader relationship is a two-way street. The receiver who interprets the story is as important as the person who created it.

Megan: I think you’re so right about the reader-writer relationship. I think one of the gifts of your books is the way readers keep finding the things they need in them. And that your books deal with so many primal, eternal themes—especially ones that speak to young people, like identify confusion. And I also think that’s why the reissues make so much sense. Your books don’t seem “trapped in amber” at all. As you say, it was mostly the “accessories” that needed updating. I wonder if some books from the 70s and even the 80s might require more “corrections” in terms of the strength of the female characters. You really give so many of your female characters a great deal of power, to take action, to drive action. To save themselves, in many cases, even if part of that means finding the right person to join their efforts. Was that important to you, as a woman? A mother? Or did it just come naturally?

Megan: I think you’re so right about the reader-writer relationship. I think one of the gifts of your books is the way readers keep finding the things they need in them. And that your books deal with so many primal, eternal themes—especially ones that speak to young people, like identify confusion. And I also think that’s why the reissues make so much sense. Your books don’t seem “trapped in amber” at all. As you say, it was mostly the “accessories” that needed updating. I wonder if some books from the 70s and even the 80s might require more “corrections” in terms of the strength of the female characters. You really give so many of your female characters a great deal of power, to take action, to drive action. To save themselves, in many cases, even if part of that means finding the right person to join their efforts. Was that important to you, as a woman? A mother? Or did it just come naturally?

LD: It came naturally. I came from a family of strong women.

Megan: What did you enjoy reading as a young woman? And did that influence you and/or your writing?

LD: I read (and wrote) a lot of poetry. I loved books about magic—The Wizard of Oz, The Chronicles of Narnia, etc. Animal stories like Black Beauty and My Friend Flicka. And the family-oriented series books that were so popular back then—the Louisa May Alcott books, the Little Colonel series, etc. Actually, I read everything I could get my hands on.

But, remember, I didn’t have much choice about what I read. That was an era before YA literature existed and readers leapt directly from children’s books to adult novels. When I started writing teenage novels I followed that

same pattern. My first book, Debutante Hill, was published in 1957 and the editor made me revise it because I had a young man of 19 (the “bad boy” in the story) drink a beer. I continued writing gentle, sticky-sweet romances until I got sick of them and decided to try writing the kind of books I wished I’d had access to when I was in junior high and high school— books that were exciting, suspenseful, and kept readers on the edges of their chairs.

My break-through book was Ransom, (Doubleday, 1966). It was about five teenagers who were kidnapped by their school bus driver, and one of them actually got shot. That book is still in print and selling well today!

Megan: Ah, so you wrote the books you wished you had been able to read, and we’re all the luckier for it! In terms of that pre-YA era, do you think that the publishers (or parents) at that time simply didn’t want to believe interests of young readers might be more complex, reflect more curiosity about the unknown? Or was it merely a lack of awareness of the market?

Given how dark and mysterious even fairy tales beloved by children are I often marvel at the notion that young adults might want only want sweet romances or adventure tales.

LD: I have no idea. I understand the craft of writing, because it’s who and what I am. The commercial world of publishing, both in the past and today, is an ongoing mystery to me. Fads are constantly changing.

When I wrote my YA ghost story, Down a Dark Hall, in 1974, it was returned to me for revisions because the victims were female and the ghosts were male, and my publisher thought feminists would object to that. When I changed the ghost of poet Alan Seeger to Emily Bronte, all was well.

When I wrote my YA ghost story, Down a Dark Hall, in 1974, it was returned to me for revisions because the victims were female and the ghosts were male, and my publisher thought feminists would object to that. When I changed the ghost of poet Alan Seeger to Emily Bronte, all was well.

Killing Mr. Griffin has been banned in certain places because of complaints from parents who (not having read the book, just going by the title) thought it would cause children to kill their teachers. Yet those are often the same parents who encourage their children to read the Bible without the slightest concern that the story of Cain and Abel might encourage them to kill their siblings.

I’ve had rejected manuscripts, yellowing in the bottom drawer of my desk for years, which I’ve then brought out, resubmitted to the very same publishers, and had snatched up, because they fell into a currently popular niche in the market that hadn’t existed when I previously submitted them.

Megan: It’s that instinctual quality that so comes through in the books, which feel organic rather than targeted, “packaged.” I actually read very few YA books as a young girl. So many seemed only interested in issues like popularity, cliques, a particular view of young love. But yours were so different—-mysterious, haunting, murky, exciting, so much more my experience of adolescence.

And they also seemed to present female relationships that were so much more complex than the usual rivalries-over-boys, homecoming queen tales.

My favorite was Daughters of Eve, which I read so many times it became dog-eared. I’d never read anything like it. The charismatic teacher and her protégées. (I now think it’s probably played a role in the book I’m finishing now, all these years later, which is about a cheerleading coach and her squad!).

What inspired you to write that book?

LD: I was inspired to write it because I wanted to write something different from anything I’d done before. The idea I got was that I would have a fanatical, charismatic adult exerting influence upon vulnerable kids who looked up to and respected that adult. I wanted it to be in a setting where other adults such as parents wouldn’t be aware of what was happening. My first idea was to have it a church youth group with the adult a charismatic male Sunday school teacher. I actually wrote five chapters and then it struck me that if Killing Mr. Griffin was being challenged by parents who thought it would make their kids violent, those same parents would claim this new book’s purpose was to keep their children from going to church. So I started over and used the same theme but steered clear of religion.

Ironically, when it was released in 1979 it was challenged by feminists who thought it was anti-feminist and by anti-feminists who thought it was feminist. I was trying to walk a nice gray line but people who feel strongly about a subject don’t want a gray line. They want it to be all black or all white.

Megan: It seems like so much of your career you’ve had to defend your writerly choices, both within publishing and without. Or perhaps “defend” is not the right word. It seems as though you had to confront many doubts that what you were writing would speak to readers, despite all evidence of the contrary. Something in your work unsettles, provokes, stirs—and I think it’s that power that also speaks to readers across generations.

I wonder if, given some of these obstacles you had to overcome in terms of publishing the books you wanted to write, if you faced any such resistance when you wrote Who Killed My Daughter?, your book about your search for the truth about your daughter’s murder. It is such a moving, powerful, painful book.

LD: My books are not nearly as controversial as many, and you can’t please everybody. A writer has to develop a hide like a rhino. If we allow ourselves to get upset every time a book is challenged we’d all be basket cases.

Mostly I’ve just written books that I wanted to write, and if publishers wanted them, great, and if they didn’t, the manuscripts went into that “deep bottom drawer,” to be pulled out, perhaps re-polished, and resubmitted at another date.

Who Killed My Daughter? was accepted by Delacorte within four days. My (then) agent was stunned, because she’d told me the book would never sell because it had no ending. I knew differently—that book was destined to be published. I also knew that I hadn’t written it myself; what I did was channeling. I sat down at the computer, placed my fingers on the keys, and “took dictation” from some ethereal source that wanted Kait’s story to be told. It’s the one book I’ve ever written in which I never altered a word. Even my editors couldn’t find a thing they wanted changed. It fell onto the pages exactly as it was supposed to.

Megan: I think that rhino’s hide is part of what I’m talking about—it feels like it comes from your internal sense that what you were interested in, the stories and characters that engaged you, would engage others.

That feeling is so strong in Who Killed My Daughter? It makes sense to me that it was a “channeling” for you, because one of its powers (its urgency, its intensity) is the feeling the reader has that it came from some deep internal (unconscious?) feeling or instinct that there was no other way to tell the story. It had to be like this.

I read on your website that you are writing a sequel now. If so, is the process different? How so?

LD: Very different. The first book was written with my heart, the sequel with my brain. The sequel will be a step by step account of our family’s personal search for Kait’s killers after the police washed their hands of the case.

Megan: I imagine you are still hearing from those affected by the original book.

LD: Constantly. In fact, we’ve heard from so many other families in similar situations that my husband and I created and maintain the Real Crimes website to help keep those other cases from becoming buried. I interview the victims’ families and help them word their stories, and Don links the documentation, (crime scene photos, autopsy reports, excerpts from police reports, etc.) That page has become a valued resource for investigative reporters and true crime shows. We do this pro bono as a way to give Kait’s short life meaning.

Megan: The responses I’ve seen to your book and to the website from families in similar situations, must feel so gratifying—though I’m sure unbearably frustrating too, to see other families suffering the same way and trying to keep investigations going.

LD: It’s heartbreaking. But don’t get me started on a diatribe about the flaws in the Great American Justice System.

Megan: Yes, it’s true. The response to your book shows the power of writing, to be sure.

So, last question, and the one writers sometimes hate to answer. Among your novels, which is your favorite and why?

LD: Over the years I’ve written 50 books, which include among other things adult fiction and non-fiction, poetry, text for pre-school picture books, humorous books for elementary age children (Hotel for Dogs, News for Dogs and Movie for Dogs in particular), lyrics for a book/CD of original lullabies, and a couple of biographies. Choosing my favorites among so many “apples and onions” would be impossible.

But if we limit it to YA suspense novels, I think it would probably be Stranger With My Face. I find the subject of astral projection fascinating, and I think that novel is also one of my best written.

Megan: Well, I just want to say you’ve fulfilled a big girlhood dream of mine, this opportunity to speak with you. Your books meant so much to me, and revisiting them has been a gift. I can’t thank you enough.

LD: Thank you, Megan. This interview has been fun for me. You’ve asked some in-depth questions that caused me to really have to think.

Originally published on The Abbott Gran Medicine Show. Click here for The Shadow Knows: An Appreciation of Lois Duncan.

Lois Duncan is an acclaimed suspense author for young adults. She has published nearly 50 books for children, including I Know What You Did Last Summer, which was adapted into a highly-successful horror film, and Who Killed My Daughter?, a non-fiction book about the harrowing experience of her daughter’s murder. Visit Lois Duncan’s website or follow her on Twitter.

Megan Abbott is the Edgar-award winning author of five novels. She has taught literature, writing, and film at New York University, the New School and the State University of New York at Oswego. She received her Ph.D. in English and American literature from New York University in 2000. She lives in New York City. Her new novel The End of Everything will be published in July 2011. Start reading on Facebook and follow Megan on Twitter.